By Michaela Pia Camilleri obo The Daphne Caruana Galizia Foundation

“The giving away of Fort Chambray and the surrounding land for the ridiculous amount of Lm10,000 a year… was and still is a scandal for many Maltese and Gozitan people.” This is how former Prime Minister Joseph Muscat described the sale of Fort Chambray before becoming Labour Party leader. Fourteen years later, he endorsed a new transfer to the Gozitan hotelier Michael Caruana.

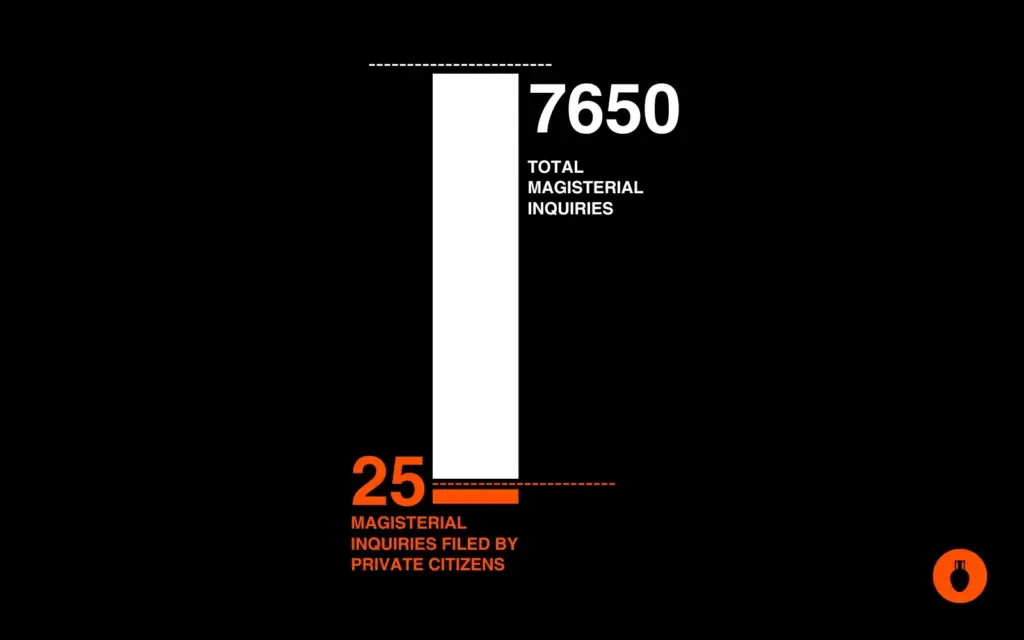

Now, the fort and the public are being sold down the river for a third time after parliament approved changes to the concession granted to Caruana in 2005. The changes, rushed through parliament without public consultation, allow him to sell his concession to a group of investors in negotiations over the site, after Caruana failed to honour significant parts of the public concession.

Last December, the Planning Authority gave the go-ahead to demolish the only British-era barracks in Gozo to make space for luxurious developments within the Fort. Several NGOs have appealed, and the hearing will be held on 25 March 2025.

Why was Fort Chambray’s sale a bad deal for Malta?

The site, covering an area of nearly 100,000 square metres, consists of three designated areas: a hotel area; a residential area; and “other areas”, being historical buildings found on the site, which include only British-era barracks in Gozo; a bakery built by the Order of St John; the polverista, built at the time for storing gunpowder; and the fortifications.

An analysis of Caruana’s 2005 contract by the Daphne Caruana Galizia Foundation shows that the PN government of the day, led by Lawrence Gonzi, granted Caruana a lenient contract.

The agreed price for the land was low, €3.5 million for nearly 100,000 square metres of land, amounting to what would today be around €35 per square metre and an additional sum of around €2,300 per month in ground rent paid over 87 years.

In 2005, Caruana agreed with the government that they would complete the project in three phases:

- Phase 1, which involved the construction of 80 apartments and villas overlooking the Mġarr Harbour area, was completed in early 2007, with the units promptly launched on the market.

- Phase 2 would include additional villas and apartments, this time overlooking the Gozo Channel.

- Phase 3 would develop a touristic area with a 6-star hotel.

However, Caruana stopped investing in the site once Phase 2 was complete, leaving things as they were.

When contacted by the Daphne Caruana Galizia Foundation, Caruana said that on 24 January 2005, he settled all the contractual amounts due, as well as all the debts, including those racked up by previous concession owners. He also said that he has never donated to a political party.

The Daphne Caruana Galizia Foundation’s requests to the Lands Authority and the Lands Minister Stefan Zrinzo Azzopardi to confirm that the payment of the premium of Lm1,500,000 and the annual temporary ground rent of Lm12,100 were all paid by Caruana and that no outstanding payments remained to be paid – were ignored.

Did Caruana breach the contract?

Green: Phase 1, Blue: Phase 2, No colour: Phase 3. Photo: Din l-Art Helwa Ghawdex.

The contract bound the developer to complete the development of the residential area in two phases: one not later than one year from the date of issue of a planning permit and the other not later than three years.

While the contract does list penalties of Lm100 (€240) for each day of default in case of failure to complete the development within the time limits, it does not specify a deadline to obtain said permits, meaning that there was never any actual timeline for the project’s completion.

After Caruana withdrew his development permit applications, he was able to stop the clock. There were no clauses in the agreement explaining what would happen in such a case.

The developer also bound himself to, at his own cost, fully restore and maintain the historical buildings on the site. These buildings have been left in a state of disrepair.

The polverista. Photos: Din l-Art Ħelwa Għawdex.

Regarding the hotel area, Caruana had one year to decide whether to build a hotel or another project. The hotel was never built. However, the contract was very weak, and he was only obliged not to leave the designated hotel area in a dilapidated state.

Where does this leave us?

We are left with several questions.

Why did the government, first under the Nationalists and then under Labour, give away valuable real estate so capriciously and with such minimal obligations for the developer?

Why were both sides of the House of Representatives so quick to give it up once again instead of fixing past mistakes?

We asked both the Labour Party and Nationalist Party whether any of the developers ever donated to them. We were met with no response.

Michaela Pia Camilleri is the Research and Legal Officer for the Daphne Caruana Galiziia Foundation.